By Irene O’Daly

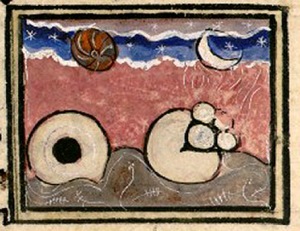

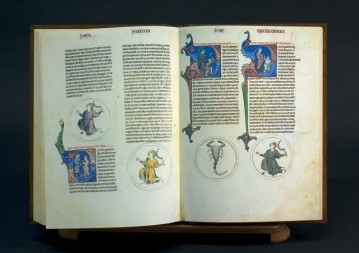

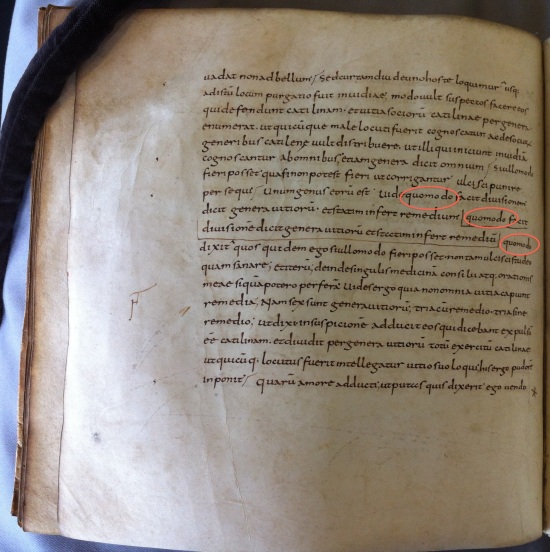

In the absence of computers and calculators, a highly elaborate system of finger-counting and gestural sign-language developed in the Middle Ages for representing numbers and facilitating conceptual reasoning. These are often represented graphically in medieval manuscripts and provide an insight into teaching and learning practices in this period. One of the most significant figures in the development of this tradition was the Northumbrian monk Bede (673/74-735) who wrote an important text on the calculation of time entitled De Temporum Ratione (725). Along with a series of calendar tables traditionally appended to it, the text often included a representation of Bede’s system of finger calculation, an elaborate version of learning to count from one to ten using one’s fingers. In this fourteenth-century version from Italy, the hand gestures are demonstrated by a series of figures, each labelled with a number. Note that the final figure in the middle row switches to using his right hand to represent the number 100 (Roman numeral C) – numbers from 1-99 were indicated by the left hand, from 100 up the right hand was used and the hands could be used to demonstrate numbers up to 9,999. There was even an indication for 1 million – the hands were clasped together with the fingers interlaced.

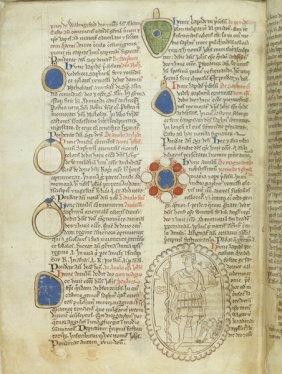

These representations of numbers depended on moving your hand in a certain way. Another version of hand-counting for the purposes of calculation was also inspired by Bede, and was less dependent on the specific placement of the fingers. The hands depicted in these illustrations helped calculations based on the nineteen-year lunar cycle. Each finger joint was assigned one year; Bede included the tips of the fingers as ‘joints’, which is why the thumb is divided into three, and each finger into four. As important liturgical feasts, such as Easter, changed date from year-to-year depending on the lunar cycles, it was useful to have a counting system literally ‘to hand’.

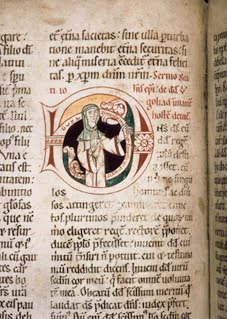

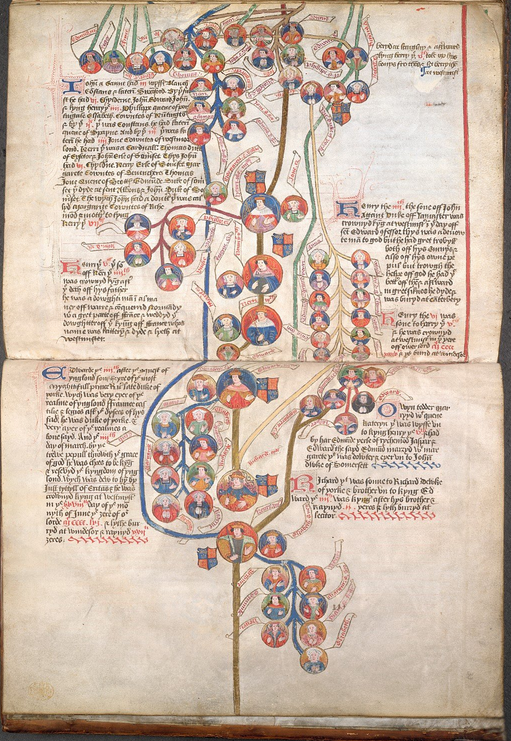

Another prominent use of hand diagrams in the Middle Ages is for the study of music. In the early tenth century, a monk called Guido of Arezzo derived the solfège method to aid monks to learn how to sight-sing with ease, assigning each note of a six-note scale a syllable (in Guido’s case, ut, re, mi, fa, sol, and la). The ‘Guidonian hand’ elaborated this system by assigning a note to each part of the hand. This allowed singers to understand how notes related to each other.

Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, MS D.75 inf, f. 6r. Image reproduced in J. Murdoch, The Album of Science, Vol. 1 (New York, 1984) p. 81

As in the case of the computus manualis, 19 locations for notes on the hand were placed on the different joints of the fingers, but as the hand was used to depict a twenty-note scale, one additional location was required, which was assigned to the reverse of the third joint of the middle finger. This is usually represented in the diagrams as an additional location hovering over the middle finger, as can be seen in this depiction.

What all these hand diagrams have in common is that they served as a physical way to represent abstract concepts. In so doing, they became valuable mnemonic devices. The versatility of the hand, with its nineteen ‘common locations’ meant that it could be used to represent a number of different things – dates, music, and even as this fourteenth-century diagram demonstrates, to facilitate prayer, with each location on the hand given a different contemplative value for ‘meditatio nocturna per manum’.

The hand, the most portable device of all, was a powerful tool for symbolic representation, calculation, and mental processing in the Middle Ages, and indicates the presence of a comprehensive, but elusive, gestural vocabulary, the full meaning of which we can only guess.

For further reading on this subject see:

J. Roberts, ‘Introduction’, The Oxford Handbook of the Reception History of the Bible (ed. M. Lieb, J. Roberts, E. Mason, Oxford, 2013)

S. G. Bruce, Silence and Sign Language in Medieval Monasticism: The Cluniac Tradition c. 900-1200, (Cambridge, 2009)

J. Murdoch, Album of Science: Volume 1: Antiquity and the Middle Ages (New York, 1984)

![A punctus elevatus sitting snugly between a [t] and an ampersand in BM Cambrai 215, f. 128](http://medievalfragments.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/bm-cambrai-2152c-f-128.jpg?w=237&h=104)

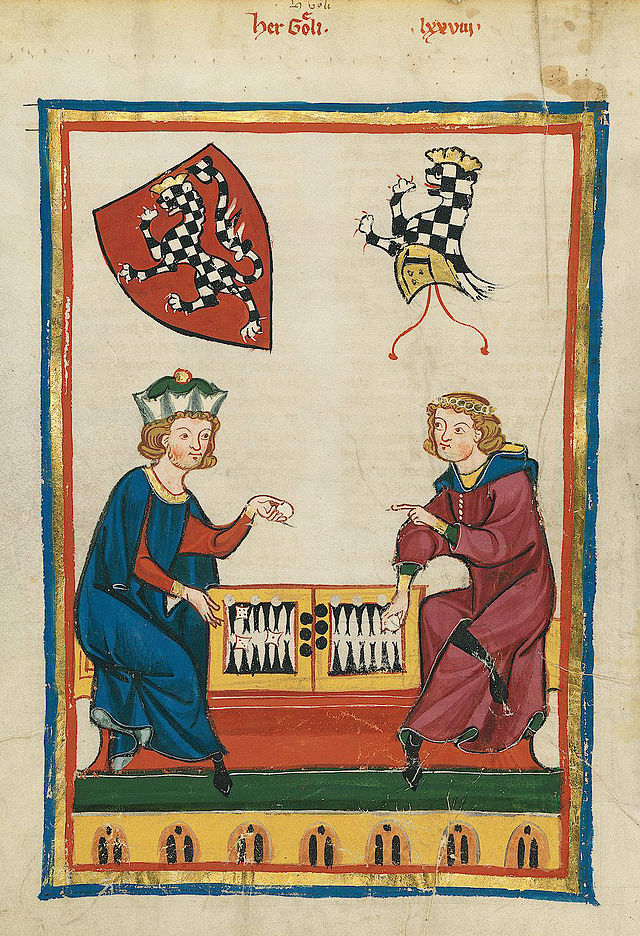

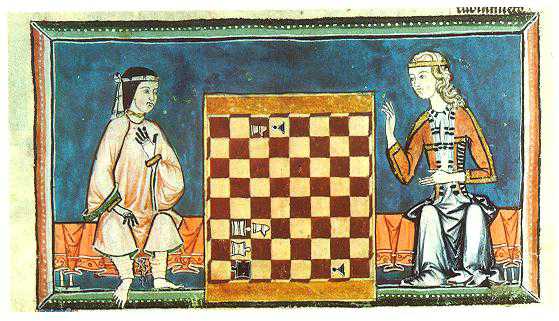

![The Carmina Burana is a collection of songs, often satirical, likely composed by rebellious Goliards [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goliard]. It contains Latin, German, and French, in two hands writing c. 1230. Here, accompanying a song about an imaginary order of lazy, gluttonous, game-playing clerics, a group of men play a backgammon-type game. Chess is also depicted.](http://medievalfragments.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/carmina-burana.jpg?w=640&h=384)