By Jenneka Janzen

In my last blog post I briefly discussed one of my favourite manuscripts, the Cantatorium of St Gall (Sankt Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek Cod. Sang. 359). It survives as the oldest complete neumed manuscript.

![Pages 24 and 25 of Cod. Sang. 359. Photo © 2013 e-codices.]()

Pages 24 and 25 of Cod. Sang. 359. Photo © 2013 e-codices.

I also mentioned that early neumes, much like those found in this manuscript, are surrounded by legend and controversy. Indeed, their stories are both illuminating and quite funny.

The history of Frankish neumes begins with the rise of the Carolingian dynasty. When Pepin the Short became King of Francia in 752, significant problems in the Frankish Church were further exacerbated by a dysfunctional relationship with Rome. Having taken the crown after a long and violent struggle, Pepin needed the legitimacy of papal support. The new pope, Stephen II, likewise needed Pepin: when Pepin vowed to protect the papal estates from the Lombards, Stephen agreed to demonstrate his support of Pepin by performing his coronation.

Pope Stephen’s visit to crown Pepin was just the beginning; he trained the community at St-Denis to practice the Roman liturgy. While suppressing local Gallican rites, Pepin then requested a collection of ‘correct’ liturgical books from Stephen’s successor Paul I, and established a Roman-style schola cantorum (song school) at Rouen. Although students of the school were trained in the Roman style, it must have been nigh impossible to ensure the new tradition remained uncorrupted by the old. There was, after all, no static notational system; melody had to be passed by voice alone, and ‘correctness’ could only be verified against visiting Roman singers. The eventual consistency of the new Frankish-Roman chant was achieved through development of a successful notational system.

![Close-up of the notation on "Alleluia . Adorabo ad templum". Cod. Sang. 359, page 53. Photo © 2013 e-codices.]()

Close-up of the notation on “Alleluia . Adorabo ad templum”. Cod. Sang. 359, page 53. Photo © 2013 e-codices.

The earliest examples of notation are from between 825 and 850. Musicologist Willi Apel explains “we cannot assume that the earliest musical manuscript that has come down to us from these remote times was actually the earliest ever written. On the contrary, the highly complex and intricate notation of a manuscript such as St Gall 359 […] marks it beyond any doubt as one that was preceded by others, now lost.” Another example, generally attributed to the late 9th or early 10th century (with some disagreement) is the incomplete Laon Gradual.

Much of what we know about the spread of Roman chant and development of neumes comes from 9th- and 10th-century writers who describe a sort of ‘chant war,’ if you will. According to Notker Balbulus in his Gesta Karoli Magni, written c. 884 at St Gall, Charlemagne asked the pope for a dozen Roman cantors to teach the monks in his kingdom. However, “being, like all Greeks and Romans, greatly envious of the glory of the Franks” they decided to sabotage Charlemagne’s goal of uniformity by each teaching a different vocal style to the Franks. Charlemagne found out that he and his kingdom’s singers had been deceived, and alerted Pope Leo. Leo recalled the offending cantors to Rome and punished them with exile or life imprisonment. Sure that any other singers he sent would be equally devious, Leo took in two of Charlemagne’s singers to be trained, and when their skill was perfected, sent them home to spread Roman chant.

(Listen to one of Notker’s own chant compositions.)

John the Deacon, a monk of Monte Cassino with ties to the papal court, recounts another colourful introduction of Roman chant to Francia. In his Vita sancti Gregorii (872-882) he describes a meeting of Charlemagne’s cantors, who accompanied him on a trip to Rome, with members of the Roman schola cantorum during Holy Week of 787. Following mass one day, a bitter conflict arose about who best performed the liturgical chants; the Franks maintained their chant was superior, while the Romans claimed their perfect style descended directly from Gregory the Great himself.

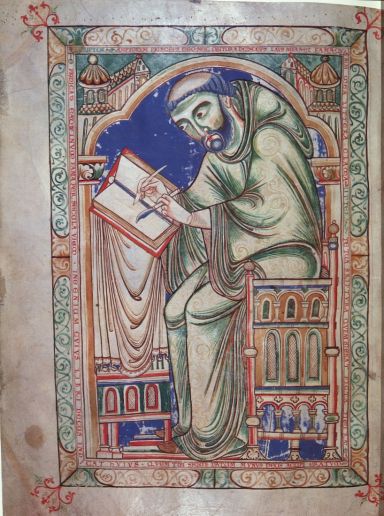

![Gregory the Great dictates chant to a scribe in the Hartker Antiphoner, c. 1000 (Cod. Sang. 390, page 13).]()

Gregory the Great dictates chant to a scribe in the Hartker Antiphonary, c. 1000, St Gall (Cod. Sang. 390, page 13).

Perhaps following a sing-off, Charlemagne deemed his own cantors inferior and insisted his kingdom adopt the ‘purer’ Roman chant style. John however maintains that the Franks were unable to accomplish this goal “because the savage barbarity of their drunken throats, while endeavouring with inflections and repercussions and diphthongs of diaphonies to utter a gentle strain, through its natural noisiness proffers only unmodulated sounds like unto farm carts clumsily creaking up a rutted hill.”

!["Oh! Sweet melody!"]()

“Oh! Sweet melody!”

While these 9th-century sources express the impetus for the introduction of Roman liturgical customs, neumes are unmentioned. The first direct discussion of neumes appears in Adémar of Chabannes’ Chronicon (1025-1028), and details the same confrontation between Roman and Frankish cantors as is told by John the Deacon. Adémar attributes the creation of neumes to the Romans: “all the cantors of the Frankish kingdom learned the Roman notation, which they now call Frankish notation”. Despite Adémar’s usually reliable accounts, no other evidence corroborates this Roman origin. Rather, Roman cantors likely taught the Franks orally, and the Franks later developed notation.

So, what were these early neumes and where did they come from? Among regional varieties, there are two general types of neumes. The earliest, called “paleo-Frankish” first appear between about 825 and 850, and are marginal or squeezed between lines of text. Unlike neumes later applied to chant books, these accompany classical poetry or illustrate small sections of musical treatises. They are likely private, localized memory aids for a single cantor or his associates, as opposed to the formal, transmittable “gestural” neumes.

Gestural neumes (so-called to reflect their imitation of the hand gestures used by the cantor-master to guide a choir) appear around the year 900; the oldest complete neumed text, as mentioned above, is the St Gall Cantatorium, attributed to 922-925. Early gestural neumes were not “literate”, that is, one could not simply read and interpret the melodies from the page without already knowing them. According to Leo Treitler, “the essentials of early notation lay not in representing individual pitches but in aiding recognition of crucial points in the text and indicating appropriate melodic gestures. This implies a sort of musical punctuation.” Pitch notation (with the development of the staff) did not exist until the eleventh, or in some places the twelfth century.

![What do you mean you can sing along? The Laon Gradual, f. 1.]()

What do you mean you can’t sing along?

The Laon Gradual, f. 1.

If notation was not a requisite step in the transmission of a new chant style, how was it used? Chant continued to be transmitted and performed largely from memory throughout the remainder of the Middle Ages, and unneumed chant books were produced long after standardization of notation systems. While the cantor relied on memory, he could now refer to neumes if he needed a reminder of how to sing the day’s chants consistently. It is likely that the very development of neumes produced their necessity; as the role of memory diminished with the popularization of neumes, neumes then likely became increasingly important to cantors.

Although the timeline, proponents, and exact use of early neumes are still somewhat unknown (and in some ways unknowable), they will most certainly continue to spark debate among researchers who approach the evidence with different questions, experiences, and the considerable body of existing scholarship laid out by passionate scholars. While manuscripts like the St Gall Cantatorium are not new to study, increasing digitization of international manuscript collections, coupled with ongoing interest in medieval chant and notation, will continue to provide ample opportunity for further discussion.

Some notes: Read Jenny’s blog on musical manuscripts here. There is actually a great album of Frankish and Roman chant curated to tell the tale of their legendary face off in Rome, called Chant Wars. Read about it here. Also, if you’d like to try singing along with the early neumes of Laon 239, a lovely tiny hand will guide you through a chant here.

Do you like neumes, chant, or Frankish liturgy? Here are some starting sources:

Apel, Willi. “The Central Problem of Gregorian Chant” Music in Medieval Europe: Chant and its Origins. Thomas Forrest Kelly, ed. (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2009): 325-332.

Grier, James. The Musical World of a Medieval Monk: Adémar de Chabbannes in Eleventh-century Aquitaine. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Hiley, David. Cambridge Introductions to Music: Gregorian Chant. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Huglo, Michel. “The Cantatorium: From Charlemagne to the Fourteenth Century” The Study of Medieval Chant: Paths and Bridges, East and West. Peter Jeffery, ed. (Cambridge: Boydell Press, 2001): 89-103.

Levy, Kenneth. Gregorian Chant and the Carolingians. Princeton University Press, 1998.

McKitterick, Rosamond. The Frankish Church and the Carolingian Reforms, 789-895. London: Royal Historical Society, 1977.

Page, Chirstopher. “Pippin and his Singers, II: Music for a Frankish-Roman Imperium,” The Christian West and its Singers: the First Thousand Years (Yale University Press, 2010): 305-326.

Treitler, Leo. Several chapters in With Voice and Pen: Coming to Know Medieval Song and How it was Made. (Oxford University Press, 2003): 131-185.

![]()

![]()